Society is in some state of chaos at the moment, and there’s so much misinformation and misunderstanding floating around. So in this blog I’m hoping to provide some of the scientific knowledge based on the research and observations. First, here are my credentials; Masters of Science in Immunology and Infectious Diseases, I’ve spent 14 years in the laboratory doing research (HIV, Tuberculosis, West Nile, Autoimmune diseases, cancer) and worked in a BSL3 laboratory. So with that out of the way, I’m going to try and stay away from giving too many opinions, talking about the politics or debating the models because there’s just too much speculation there. So if you’re interested just in the scientific research about the virus, the immune system and the current case study numbers hang on, this is going to be a long one (all references cited will be at the end).

Background

In early December 2019 a cluster of pneumonia cases appeared in Wuhan, China with clinical characteristics similar to SARS-CoV-1. Of the initial patients studied the mortality rate was extremely high (10-15%, now estimated closer to 2-3.5%), which gave rise to great concern that this virus would be a serious health issue. Sampling from the initial patients and sequencing identified the causative agent as a novel (new) coronavirus that was originally named 2019-nCoV (Huang C et al). Subsequent sequencing and analysis of the virus from those original cases showed that the founding virus has similar characteristics to coronaviruses found in bats, but is also related to those found in pangolins. There are currently two sub-strains of the virus circulating in the population; S-type and L-type. The S-type is thought to be the founding strain, while the L-type is a slightly altered variant that is now the predominant virus circulating in the population (70% of cases), though the consensus sequence for both strains only differ by a few base pairs (Tang et al). As of now (3/18/20) there is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can sustain infection and spread through any other animals other than humans. As of 3/18/20 China has experienced 80,894 confirmed cases on COVID-19 (disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 formerly 2019-nCoV) and 3,237 deaths from the virus (worldometers.info). While daily number of new cases in China has significantly waned in recent weeks, it has spread to the rest of the world and is currently spreading rapidly throughout Europe, the Middle East and the United States.

How the Virus Spreads

Viruses can spread by either direct (touching, kissing, sex) and indirect (coughing, sneezing, aerosols) methods. Early on during the epidemic of SARS-CoV-2 it was realized that the virus was capable of spreading by indirect contact and possibly survived in aerosols. Though the primary route of transmission is still thought to be direct or close contact with an infected individual. Studies showed that aerosolized liquids containing SARS-CoV-2 could survive on surfaces (specifically plastic and steel) as long as 72 hours in a controlled laboratory setting (Doremalen et al). Though the half-life of the virus on all surfaces was 16 hours or less. Meaning that while the virus can be detected up to 3 days after deposition most of it dies much earlier, though we don’t know exactly what the survival time in a natural environment is. The main take home from this should be, the virus can be transferred from one host to another fairly easily and surface contamination can be an issue if an infected person sneezes/coughs, so cover your mouth and clean common areas! One thing that has made the virus especially difficult to track and control is the presence of what are known as asymptomatic carriers. These are individuals who become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and are contagious without showing any symptoms (Bai et al). Thus, while they appear fully healthy, they are in fact vectors for the disease without even knowing it. Additionally there can be long incubation times between becoming infected and showing symptoms, thus allowing people to spread the viruses unknowingly.

Preventative Measures (WHO.int)

Standard hygiene rules apply for SARS-CoV-19;

Wash your hands frequently.

Clean common surfaces in shared areas.

Cover coughs and sneezes with an elbow or arm.

Do not touch your nose, eyes and mouth (this is how the virus gains access to the body).

Social distancing (the practice of staying 2m away from potential contacts).

Stay home if you’re sick and self-quarantine. This one is very important and something Americans do not do well.

The question of using masks and gloves has come up numerous times, so I’m going to try and dispel some of the rumors and misinformation. These items are known as PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) to those in healthcare and the medical sciences. They are used to protect one’s self from infectious and hazardous materials when used properly. Both N95 masks (fitted and tested, designed to filter out 95% of microparticles) and surgical masks (loose fitting masks that cover your mouth, no seal) are designed to create a barrier between the user and the surrounding environment. N95 masks when worn properly will filter out most particulate and infectious matter, protecting the wearer, when USED PROPERLY. Proper use does not include wearing it around your chin, pulling it off your nose to breath or touching the mask with unwashed hands, in short most of the public is not trained well enough to properly use these and thus negates a lot of the benefits they can provide. Surgical masks on the other hand are designed to protect those surrounding the user by blocking some of the aerosolization of material, they ARE NOT designed to protect the user from inhaling microparticles (same goes for cloth masks) (Balazy et al). The reason the government does not want the public using and hoarding these disposable masks is that there is a HUGE shortage for our healthcare workers, the people who have to take care of the sick and injured on a daily basis (which may be you). They come into contact with the infectious and at risk at levels exponentially higher than the average person and if they don’t have these protective equipment then it’s almost a certainty they’ll get infected, and then either be forced to take time off (leaving our hospitals understaffed) or infect those around them such as patients who are at risk. If you’ve been hoarding masks or bought a bunch think of donating them to your nearby hospital, every nurse or doctor I’ve spoken with says they are rationing and running very low on these supplies. If you need to wear a mask buy a cloth reusable mask (and wash it regularly) in order to protect those around you from anything you might be carrying. As with the N95s above, disposable latex and nitrile gloves are not very practical or helpful for most people. Every time you touch your body, your cell phone, your hair, your mask on your face, you contaminate the gloves and spread that contamination around. Save yourself the waste and trouble and just regularly wash your hands.

Symptoms and Testing

The main symptoms as outlined by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) are; fever, cough and shortness of breath along with a host of other minor symptoms (CDC.gov). What sets SARS-CoV-2 apart from influenza or the common cold is the lower respiratory involvement. Symptoms usually appear in 2-7days, but there have been cases where symptoms are very delayed (beyond a week). The state of Colorado recommends that if you have these symptoms or are concerned due to exposure to a positive case to call your primary care doctor first, do not go to an ER unless it’s an Emergency.

Once the virus enters the body it binds to ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2) receptors on vascular endothelial cells and uses these cells as a host to replicate. ACE2 receptors are also found in the lungs, kidney and GI tract, all locations known to harbor coronaviruses (Jia et al). In addition to the more general symptoms, in moderate to severe cases pulmonary inflammation and damage are seen and these are considered the more critical issues when looking at long term prognosis. CT scans of the lungs were found helpful in diagnosing patients with more advanced disease (Zhu et al). Patients over the age of 65 and those having a host of other chronic disorders (hypertension, diabetes, auto-immune diseases, immunocompromised) are more likely to progress to severe COVID-19 disease than those without (Zhou et al). Though recently it has been seen that even younger patients can have lasting pulmonary damage beyond disease resolution.

Which brings us to the next issue, testing…oh testing….. When the epidemic first began in China researchers isolated and sequenced the viral genome (this is an RNA virus). Allowing them to identify unique sequences in the virus that they could use as a genetic finger print. In January of 2020 a group at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin released information on an assay that would guide the creation of the first large scale PCR testing to be adopted by the WHO (Corman et al). Since then several other countries have released different versions of the test. Since January over 1million tests have been run around the world, with China (320,000), South Korea (286,000) and Italy (148,000) leading the way (ourworldindata.org). Sadly the estimates in the United States are that only 41,000 people have been tested. I say ‘estimates’ because right now we have no National testing strategy or centralized facility monitoring our testing. Tests are being run by government labs, hospitals, private diagnostic labs and even some private biotech companies have created their own tests, but the short of it is there’s no central coordinated effort as of 3/18/20. If you’re interested in reading more about what went wrong with our testing, check this article from the New Yorker.

Which brings us to how can you get tested? Well, the short

answer is most people can’t. Because of testing shortages the guidelines on who

can get tested vary wildly from state to state and county to county. The standard

criteria in Colorado as of 3/18/20 is that you must have an order from your

healthcare provider, stating known contact with another infected patient and/or

presenting with symptoms. Even if you do meet that criteria there’s no guarantee

you can or will get tested right now, I personally know several people who fit

the criteria but have been turned away to self-quarantine and monitor. So how

do you know if you are infected with the virus? Well, in the United States right

now you really don’t, and in lieu of broader testing to identify the spread of

the virus social distancing and limitations on group gatherings (including concerts,

bars, restaurants) have been put in place.

Treatment Options

Right now there’s no fully validated and approved treatments

for COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). For those with more mild forms of the disease the

CDC recommends; quarantine, rest, monitor your symptoms and continue with the

preventative measures listed above. For those with more severe symptoms go to

the hospital for care.

As of 3/18/20 there are numerous companies in the early stage of testing vaccines against COVID-19, one has even begun Phase I human trials, which simply looks at whether or not the vaccine is safe in humans, it’s a long way from mass production though. There are also several approved medications that are being tested in Phase II and III clinical trials in patients suffering from COVID-19; Remdesivir, Chloroquine and Favipiravir appear to be the most promising. All three were originally developed for other diseases (Ebola, malaria, influenza) but are being repurposed to fight COVID-19 and have shown promise in early patient testing. It’s quite common for drugs to be tested and used for numerous different indications, because this expedites testing as the safety has already been proven in previous studies. EDIT:

Because Trump and the FDA made specific announcements about Hydroxychloroquine today (3/19/20) I’ll add an extra note here. Hydroxychloroquine has been been used as an anti-malarial (parasite) for almost 70 years, and is also used to treat Lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, so you might ask, how does this drug help us fight a virus??? The drug alters the pH inside special compartments inside our cells (for the scientist; lysosomes, endosomes and the Golgi) having an affect on several pathways. One such pathway is the process of breaking down antigens and presenting them to immune cells (Fox et al). For autoimmune diseases this means the drug helps slow the immune response to your own body, but this is counter productive to fighting a virus that we want to kill, so what gives? Ah, but there’s an alternate pathway that the drug affects, modification of proteins in the Golgi. These modifications are essential for viruses to replicate and produce more functional virion! So the drug does function to slow down some parts of the immune system (not all) BUT it also serves to reduce viral replication (in experiments with HIV showed modest reduction, SARS-CoV-2 specifically has not been tested yet) (Romanelli et al).

Immunity?

With most infections, your body has two stages of response. First is the non-specific innate immune response where our body recognizes that there’s a foreign invader (bacteria, virus, parasite, etc) and attempts to kill it. Sometimes the number of the microbe is too great and they infect and spread in the body causing disease. All infectious organisms have a minimum infectious dose that’s required to get a person sick, though this exact amount varies from person to person, for route of entry and is different for each microbe. Once the initial non-specific response fails our body goes into overdrive to try and kill off the rapidly replicating organism. This includes running a fever to burn the pathogen out and creating a pathogen specific memory response via T-cells and B-cells selection. These specific memory responses are the backbone of what is known as pathogen specific immunity, or our ability to fight off a disease. As of now (3/18/20) it appears as though people who survive and recover from COVID-19 are immune to the virus. Recently there have been news articles about how several recovered COVID-19 patients have retested positive for the virus, these cases most likely fall into one of two categories; first that the patients were released prematurely from the hospital and thus still had low levels of virus remaining in their system, second the recovered patient came into contact with another infectious patient who transferred the virus to them allowing them to retest positive. Being immune does not mean that another person who is infected can not transfer the virus to us, it simply means our body is able to destroy the invading pathogen before it causes disease, this is how a vaccine works. Note that in both cases the affected individuals did not get sick a second time (as far as we know) and for those who become immune it is not believed they can further spread the virus once fully recovered.

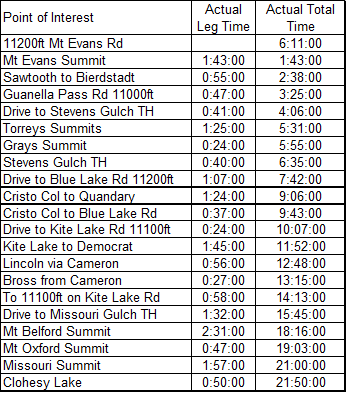

Current Statistics (3/18/20)

As of 10pm on 3/18/20 there have been 219,243 people who have tested positive for COVID-19, 124,530 cases are still active (6,814 are in serious/critical condition), 85,745 have recovered (mostly in China) and 8,968 have died (worldometers.info). The current world wide mortality rate stands at 4.09% but as many have and will point out that is a flawed number because of the lack of testing and the lack of understanding what the actual case load is. COVID-19 is different than other viral infections we have because it does seem to be killing patients at a higher rate than other viruses currently in circulation. On Wednesday March 18th alone 976 people worldwide died from COVID-19, that’s a pretty astounding number, especially considering the pandemic is still spreading in many countries. In the United States we had 2,848 NEW cases on March 18th, and that’s with our testing infrastructure greatly lagging and many people not being tested. What makes the potential for this virus so scary is that it has a disproportionately negative effect on those who are elderly, immunocompromised and those who have a number of specific risk factors that depress the body’s normal immune responses. The pandemic is far from over and while none of us know exactly what will happen, it’s not looking good in the short term.

Cited Literature and Sources

Bai et al, Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA Network, Feb 2020.

Balazy et al, Do N95 respirators provide 95% protection level against airborne viruses, and how adequate are surgical masks? American Journal of Infectious Control, March 2006.

cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/index.html

Chiang et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by hydroxychloroquine: mechanism of action and comparison with zidovudine. Clinical Therapeutics, November 1996.

Corman et al, Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance, Jan 2020.

Doremalen et al, Aerosol and surface stability of HCoV-19 (SARS-CoV-2) compared to SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine, March 2020.

Fox et al, Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, Oct 1993.

Huang et al, Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, Jan 2020.

Jia et al, ACE2 Receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depends on differentiation of human airway epithelia. Journal of Virology, Dec 2005.

Newyorker.com/news/news-desk/what-went-wrong-with-coronavirus-testing-in-the-us

Ourworldindata.org/covid-testing

Romanelli et al. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine as Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) Activity. Clinical Pharmaceutical Design, 2004.

Smith et al, Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks in protecting healthcare workers from acute respiratory infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, Dec 2015.

Tang et al, On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. National Science Review, March 2020.

Wang et al, Establishment of a reference sequences of SARS-CoV-2 and variation analysis. Journal of Medical Virology, March 2020.

Who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Zhou et al, A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature, Feb 2020.

Zhou et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet, March 2020.

Zhu et al, Initial clinical features of a suspected Coronavirus disease 2019 in two emergency departments outside Hubei, China. Journal of Medical Virology, March 2020.