Topics:

Vaccines

Therapeutics

Reinfection and Immunity

Children and Schools

Looking Forward

Well, a lot has happened since I last wrote a Covid related piece, and a lot of important things have come to light very recently. In the past six months those of us in the United States have endured several waves of outbreak, and currently as of this writing we’re in the middle of the worst outbreak since the initial outbreak in April/May (Nov 11th, 2020; 144,000 New Cases, 65,000 hospitalized patients and 1400 New Deaths, John’s Hopkins data). There are many possible reasons for this proliferation in infections, but it’s not specific to a political party, demographic or portion of the country. Rather than argue about that, I’ll simply say, it doesn’t seem like people are acting responsibly and we’re going to pay the price, as death rates always lag a few weeks behind infections.

In the following paragraphs I’ll outline a lot of what has happened with the development of the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines (including immunity, data, side effects, and timelines), what we’ve learned about the virus and how we’re treating it with new therapeutics, what the data tells us about how safe schools are and lastly some additional important notes about transmission. Note that this write-up is based on the information known as of 11/11/20, and I’m sure in the weeks following a lot of new information will come out. So let’s dive right in to the topic on almost everybody’s mind….are the vaccines going to work, when will they be approved and how long before ‘I’ can be vaccinated?

SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Development and Trials:

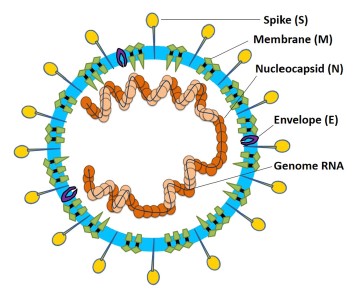

The big headline on 11/9/20 was that interim data on the Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine “BNT162b2” shows 90% efficacy in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection. Before we jump to too many conclusions, let’s take a step back and talk about how we got where we are and what we know. Since the release of the first genetic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 way back in January 2020 (10 months ago!) the scientific community has been working at a feverish pace to learn everything we possibly can about the novel coronavirus, turning out a mountain of research that would normally take a decade, in just a year’s time. A search for scientific articles containing “Covid” on pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ returns 68,494 hits! On top of this, many of the biggest Biotech companies in the world have dedicated huge proportions of their of their staff (often working lots of overtime) to the single task of solving this public health crisis, so believe me when I say this has been a truly unprecedented time for Science.

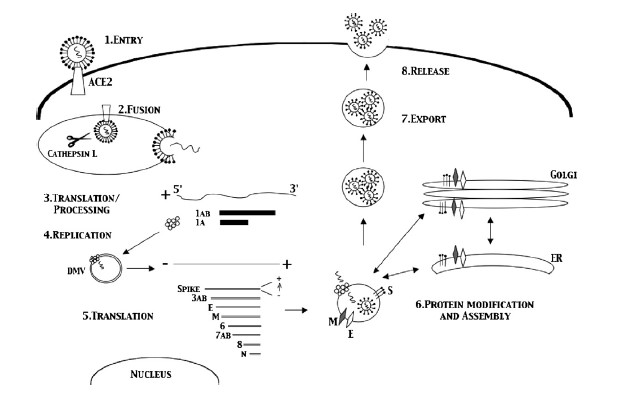

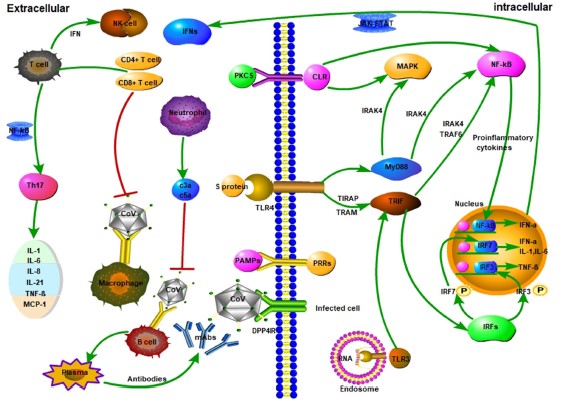

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have progressed along timelines never seen before, partially because of this massive effort by the scientific community to execute multiple steps in the pipeline simultaneously, building off previous research on SARS-CoV and utilizing advances in vaccine development discovered in recent years. But questions remain, will the vaccine work, what kind of immunity is possible against SARS-CoV-2 and how long will it last? A lot of research has focused on assessing two major pieces of the human memory immune response to viruses; Bcells/Antibodies and Tcells. Most people have heard of antibodies (and the Bcells that produce them), and while most of the literature has shown that moderate to severe cases of Covid-19 lead to strong neutralizing antibody responses (Long April 2020), the durability (how long they last) is still open for debate and seems to depend on the severity of the disease experienced (Long June 2020). Thankfully the other arm of the memory immune response (CD4+ and CD8+ Tcells) seems to be far more robust and durable, and many studies have shown strong levels of anti-viral activity in a wide array of Covid-19 patients, even those who become seronegative (negative for antibodies) (Sekine June 2020, Le Bert July 2020, Grifoni June 2020). So this brings us back to vaccines, and a growing mountain of evidence that a well designed vaccine that leads to a robust immune response can subsequently lead to immunity against Covid-19.

There are currently 10 vaccines in Phase 3 clinical trials (raps.org), this is the final Phase of testing in which a large number of patients are vaccinated with the aim of looking at how effective the test vaccine is at preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to a placebo control. Each trial is set to vaccinate upwards of 60,000 of people and won’t close down until a certain number of people become infected (doesn’t matter if they’re placebo or test vaccine). The threshold for the Pfizer trial is set at 164 infections, and the trial currently sits at 94 positive Covid cases, meaning they’re targeting another 70 positive Covid infections in the study before they close down and analyze all the data (though this could happen sooner). Early data from Phase 1&2 Trials of the successful vaccine candidates have shown a strong and consistent induction of the immune system, with SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody titers and SARS-CoV-2 reactive CD4+ Tcell levels being as high or better than those found in patients who have recovered from natural Covid-19 disease (Folegatti July 2020, Anderson Sept 2020, Sahin Sept 2020, Walsh Oct 2020). While the long term efficacy (>1year) of these responses is not known at this time, these trials are set to follow patients out for 2 years post-vaccination, and so far early returns (3-4months post-vaccination) are all promising that the vaccines create durable responses that will last for at least some time (TBD).

So we might have an approved vaccine before the end of the year (maybe even several), what next? Well thankfully for the general public many of these companies have already started building production capacity and scaling up production, banking on a successful Phase 3 trial (a big gamble). This means that if/when their vaccine is approved they are ready to start shipping vials almost immediately. Both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are mRNA vaccines, a relatively new technology that is MUCH faster to produce than traditional protein based vaccines. Problem is, there are some 7.5billion people to vaccinate, and initial estimates from Pfizer are to have enough vaccine for 50million doses (25million people) this year, that’s not a lot when distributed around the world. The WHO has a plan to evenly distribute the vaccine across all countries, but it remains to be seen if wealthier nations allow this to happen (WHO.INT/). Here in the US a team led by the Army have already worked out a supply chain and distribution plan to the different states, and then it’s up to each state to create a prioritization plan on who gets vaccinated first. Here in Colorado a rough draft of this plan has already been submitted to the CDC for approval, check this link for the full draft.

Skip to page 22-23 if you want to see the tiered priority list of who will be vaccinated first. In short the higher risk professions and people will be given first priority, even then estimates are that Colorado will receive 100,000 doses in the first shipment, enough to vaccinate 50,000 people, only a portion of those in Tier 1A. For those of you in the healthy general public, expect to wait until next Spring/Summer to get vaccinated (these timelines are still very fuzzy).

So whenever your turn comes up, there is a big question of what to expect from this vaccine. First off, there might be several choices available, and it remains to be seen if they all have similar efficacy and longevity. Second, there are different kinds of vaccines (mRNA, whole inactivated, subunit vaccines, hybrid vectors, etc) (Krammer Sept 2020). We don’t yet know how they stack up against each other, so I won’t elaborate any more at this time on them, but welcome questions about the different types if anybody has them. None of these vaccines are using live replication competent virus, so they do NOT cause infection. Two things to note about the vaccines in full disclosure, it’s not going to be as convenient or as comfortable as other vaccines we’re given in a more routine manner. This is part of what was sacrificed to make these timelines possible. Note, this DOES NOT in any way mean safety corners were cut or that regulatory steps were skipped, but rather it means that the comfort and patient experience isn’t quite as clean or easy. Many patients receiving the two dose vaccine regimen (Oxford, Moderna, Pfizer) report mild to moderate flu like symptoms within 24hours of administration; fever, fatigue, headache, etc. The symptoms are reported to go away within 24hours and are indicative of the body mounting a very strong immune response against a very strong vaccine, a good thing! Just be prepared to take a day off after receiving the vaccine, because there’s a good chance it’ll knock you on your ass (very short term).

Therapeutics

Other big news that came out this week was that Eli Lilly’s monoclonal antibody therapy against Covid-19 was given Emergency Use Authorization, though it is only being prescribed to elderly and high-risk patients, but at no charge (per US Government). Thankfully this is one of several therapeutics that have been shown to be efficacious in reducing the severity of Covid-19. Therapeutics can be divided up into those that act during the early stages of infection aimed at reducing the viral load and those acting during the later stages of infection that aim to minimize the damage caused by the immune response. In the former are anti-viral drugs such as Remdesivir (Gilead) (Spinner Aug 2020), monoclonal antibodies like Bamlanivimab (Eli Lilly) and REGN-COV2 (Regeneron, still in Phase 3) and a host of other anti-virals and biotherapeutics progressing through clinical trials. Convalescent plasma, while initially promising and helpful for some patients, is becoming less commonly used due to the inconsistent levels of neutralizing antibodies in donor patients (Agarwal Oct 2020). All of these treatments have been shown to be most efficacious when administered during the early stages of infection, before the disease reaches critical levels. Once the infection becomes more severe, requiring hospitalization, most of the therapeutics above have been shown to have minimal impact on the cytokine storm induced pathology, but this is when dexamethasone comes into play. A corticosteroid first approve in 1958, it acts as an immunosuppressant to help control the body’s over-reactive immune response to the virus that causes much of the late stage disease pathology, keeping many patients off ventilators (Tomazini Sept 2020). While none of these therapies are cures they have been instrumental in helping save some patients and in reducing the overall mortality rate. THIS is what the lockdowns did, they bought the Medical and Scientific community time to catch-up so that we could save more lives, though we still have a long way to go.

Reinfection and Immunity (Update)

Another big question that has arisen recently is about the potential for long term immunity and reinfection, the latter was recently proven by several case studies in Nevada, Hong Kong, Belgium and Ecuador (Iwasaki Nov 2020). First let’s start with what’s been learned about the immune response (for a more details on the immunology/virology, see my previous post). SARS-CoV-2 is a fairly sinister virus, in addition to asymptomatic/pre-symptomatic spread, the immune responses caused by it are quite variable. In many asymptomatic and mild cases the levels of neutralizing antibodies and length of seropositivity were shown to wane quite rapidly (Long June 2020), while those who had more severe disease had longer lasting humoral responses. Thankfully as I briefly introduced above, Tcell immunity seems to be more consistent across all infected patients (Sekine June 2020) and plays a major role in the memory response to the virus. Research has also shown that some people who have been previously infected by other coronaviruses have cross reactive memory responses to SARS-CoV-2 (Sette Aug 2020, Mateus Aug 2020), and that children may harbor higher levels of these cross reactive antibodies, a potential reason they are more resistant to Covid-19 (Ng Nov 2020). Preliminary data from one paper also showed that immune priming using the seasonal influenza vaccine can help promote immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. This is very preliminary lab data, and IS NOT inducing specific responses, but rather just an immune priming effect, similar to an adjuvant (Debisarun Oct 2020). This cross reactivity from other coronaviruses and immune priming from the flu shot DO NOT confer immunity, but may be part of the reason some people have more mild disease than others, though these hypothesis are still under investigation.

But if the body creates all these immune responses (some durable), how are people getting reinfected? Unfortunately for the handful of confirmed case studies we (Scientist) don’t know the exact answer. It’s possible the individual immune response was incomplete and thus proper memory cells were not created or maybe they were infected with such a high dose the memory response was overwhelmed? Thankfully, while viral sequencing of the Nevada case showed two separate viruses during the first and second infection, the mutations in their genomes did not appear to affect the antigenic sites the body recognizes; in short, mutation does not seem to be the reason for reinfection. Now, before you spin yourself into a frenzy, we’re talking about less than a dozen confirmed cases worldwide. If reinfection were a major issue (right now) we’d be seeing thousands of cases, not a handful, and these outliers were inevitable. So for now there is no need to panic about this topic, though it remains to be seen how long (beyond 1 year) immunity lasts and how stable the virus will be long term. So far due to proof-reading enzymes in the virus, and lack of selective pressures the virus seems to be fairly stable (Romano May 2020). Research on both these topics is ongoing, and as we get further out from the initial outbreak more will come to light.

Children and Schools

Now on to something a little more contentious, what role do children and schools play in the spread of the virus and is it safe to open up schools? I’ve spoken with many parents and teachers about this, and have heard stories on both sides; inability to work when kids are home, forcing a 6yo to do 5h/day of zoom (horrible), trying to educate one’s kids while working from home, teachers being given inadequate PPE to setup safe environments, teachers being guilted into working because if they don’t they’re responsible for our kids failing and on and on. It’s a terrible situation all around, so rather than focus on the politics, I’ll try to focus more on the research about how infectious are children and whether or not schools cause outbreaks.

By now most people are aware that children (0-19) rarely get severe disease and their risk of dying is very low. But the role of those under the age of 19 in spreading the virus is not so simple. Younger children (<4 or <6 in some papers) do not seem to be very strong vectors for Covid-19, meaning they are less likely to be infected and to transmit the infection to others. Older children (6-13) on the other hand were far more likely to become infected and transmit the virus, while young adults (14-19) experienced similar disease progression to people in their 20s (Goldstein July 2020). Though one study out of Duke did find that children of all ages (0-19) had similar nasopharyngeal viral loads (Hurst Sept 2020), but did not relate this back to infectious spread. So for children the story is more complicated because there does seem to be age related variability in regards to symptoms, though they can still become infected and transmit the virus in many instances.

Now the big question, what do the case studies from schools that have reopened show about the potential for Covid-19 outbreaks in schools? Unfortunately the answer again isn’t completely clear, partially because schools are reopening with a variety of mitigation measures, different levels of community spread and with different plans for testing, isolating and tracking outbreaks. Case studies out of Germany and Australia concluded that transmission within schools was fairly low IF community spread of the virus remained low AND rapid testing and contact tracing protocols were followed (Ehrhardt Aug 2020, Macartney Aug 2020). In both of these case the schools were running at reduced capacity, and following rigorous cleaning protocols, physical distancing and mask policies in some instances. Another case study out of Luxembourg found that during a community outbreak, secondary infections were transmitted throughout schools, though no large super-spreader events occurred in the schools (due to tracking and tracing programs) (Mossong Oct 2020). Overall the literature seems to agree that school related outbreaks are far more common in secondary and University level facilities (Goldstein July 2020), and while outbreaks do happen in younger children they do not seem to spread as rapidly. Measures such as reduced class sizes, physical distancing, rigorous cleaning, hand washing, mask wearing and testing and contact tracing will help limit any potential outbreaks. Though all of this is also contingent upon the level of community spread, and no study has tested or recommended reopening schools during larger and uncontrolled community outbreaks (like what’s happening in the US right now). The State of Colorado tracks all our larger outbreaks that are associated with a single facility/school, and if you look at the data you’ll notice many schools listed, but also many other businesses, events and gatherings.

Final Notes and Looking Forward

While there is a ton of promising data about vaccines, therapeutics, mitigation measures that help us control the spread, we are far from done with the pandemic. With cases, hospitalizations and deaths spiking all across the United States things are promising to get worse before they get better. Winter will bring the confounding issues of people being stuck indoors more often, influenza returning to the Northern Hemisphere (get your flu shot!) and the holidays (which promise to see lots of people traveling). If you have to travel I’d highly recommend you read my earlier post about navigating airlines, and be aware of the risks you are taking (United has fully booked flights right now, every seat). While airlines have been shown to not be high risk by themselves (Freedman Sept 2020), several outbreaks, including a large one on an Irish airline (59 cases), should be stark reminders of what can happen when people let their guard down (Murphy Oct 2020). Pandemic responses are not just about each person protecting themselves, but about all of us protecting those around us as well. Boulder County just went back into ‘Safer at Home: Level Orange‘, heavily restricting gatherings (2 households/10 people max) and further restricting other events and businesses. While we in the Scientific/Medical community are Catching up with Covid, it appears Covid is catching up with the general public….it’ll be a race to see who comes out on top.

Citations:

Agarwal et al, Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid-19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicenter randomized controlled trial (PLACID Trial). BMJ, Oct 22, 2020.

Anderson et al, Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. NEJM, September 29, 2020.

Eli Lilly, Lilly’s neutralizing antibody bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) receives FDA emergency use. Press Release, 11/11/20.

Debisarun et al, The effect of influenza vaccination on trained immunity: impact on COVID-19. medRxiv pre-print. October 16, 2020.

Ehrhardt et al, Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in children aged 0 to 19 years in childcare facilities and schools after their reopening in May 2020, Germany. Eurosurveillance, September 10, 2020.

Folegatti et al, Safety and immunogenicity o ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single blind, randomized controlled trial. Lancet, Vol 396: 467-478. July 20, 2020.

Freedman et al, In-Flight transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a review of the attack rates and available data on the efficacy of face masks. Journal of Travel Medicine, 1-7. September 18, 2020.

Goldstein et al, On the effect of age on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in households, schools and the community. medRxiv pre-print, July 26, 2020.

Grifoni et al, Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell, 181; 1489-1501. June 25, 2020.

Guo et al, Long-Term Persistance of IgG Antibodies in SARS-CoV Infected Healthcare Workers. MedRxiv preprint, Feb 2020.

¬Han et al, Clinical Characteristics and Viral RNA Detection in Children with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Pediatric, August 28, 2020.

Hurst et al, SARS-CoV-2 Infections Among Children in the Biospecimen from Respiratory Virus-Exposed Kids. medRxiv pre-print, September 1, 2020.

Iwasaki et al, What Reinfections mean for COVID-19. Lancet Infectious Diseases, November 6, 2020.

Kaur et al, COVID-19 Vaccine: A comprehensive status report. Virus Research, Vol 288. August 13, 2020.

Krammer et al, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature, September 23, 2020.

Le Bert et al, SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature, Vol 584, August 20, 2020.

Long et al, Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nature Medicine. June, 18 2020.

Macartney et al, Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Australian educational settings: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolescent Health, August 3, 2020.

Mateus et al, Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science, August 4, 2020.

Mossong et al, SARS-CoV-2 transmission in educational settings an early summer epidemic wave in Luxembourg. Pre-print, October 2020.

Murphy et al, A Large National Outbreak of COVID-19 Linked to air travel, Ireland, Summer 2020. Eurosurveillance, Oct 6, 2020.

Ng et al, Preexisting and de novo humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Science, November 6, 2020.

Romano et al, A Structural View of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Replication Machinery: RNA Synthesis, Proofreading and Final Capping. Cells, Vol 9(5): 1267. May 20, 2020.

Sahin et al, COVID-19 vaccine BN162b1 elicits human antibody and Th1 T cell responses. Nature, Vol 586. October 22, 2020.

Sekine et al, Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild Covid-19. bioRxi preprint. June 29, 2020.

Sette et al, Pre-existing immunity to SARS-CoV-2: the knows and unknowns. Nature Reviews, Vol 20: 457-458. August 2020.

Spinner et al, Effects of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients with Moderate COVID-19. JAMA, August 21, 2020.

Tomazini et al, Effect of Dexamethasone on Days Alive and Ventilator-Free in Patients with Moderate or Severe SARS Distress Syndrome and COVID-19. JAMA, September 2, 2020.

Walsh et al, Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based COVID-19 vaccine candidates. NEJM, October 14, 2020.

Willyard, Ageing and COVID Vaccines. Nature, October 15, 2020.