There’s been a lot of debate and misinformation floating around about the use of masks for the general public as a measure to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, specifically Covid-19 in the United States. Do they help, do they not? Is an N95 really better than a surgical mask, is this better than a cloth mask? How and when should they be used? On 4/3/20 the CDC in the United States finally came out with a blanket recommendation that ALL citizens of the United States wear some sort of face covering whenever in public. This was a dramatic change of direction from the previous recommendation that masks were completely unnecessary, except for front line hospital workers and for the infected. In this rendition of Eric’s Science Corner I’ll do my best to present some of the data and studies that have looked at the questions above, in an attempt to clarify the misunderstandings and the mixed messages. The topics I’ll try and cover are; what are the different types of masks and what are they designed to do? How useful are the different types of masks for the general public? And finally, a few best practices on how to wear and use a mask or face covering. Rule #1, just ignore anything Donald Trump says, now on with the info.

Defining Mask Types

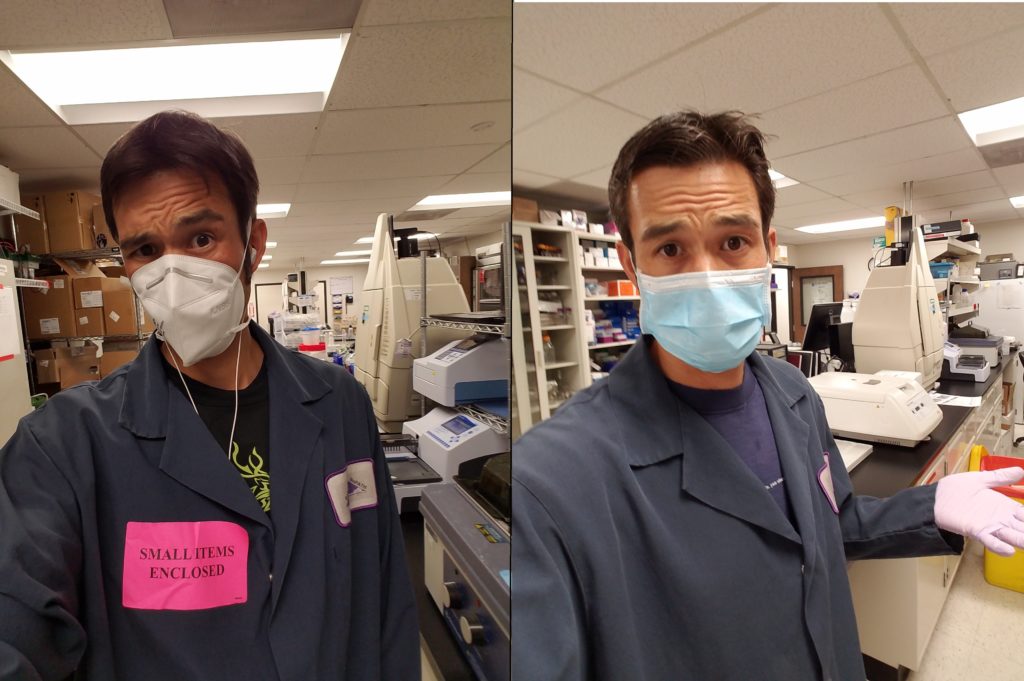

To start there are three main categories of face masks that I’ll be discussing; fitted N95 respirators, professional grade surgical masks and cloth masks (variety of materials). There are numerous sub-categories for each and also other types of protective face wear I won’t discuss because they aren’t really relevant to the general population, only to those in the hospitals and those of us who work in laboratories. The first type is the fitted N95 respirator, these are face fitted respirator masks that have been certified to filter out approximately 95% of aerosols and particulate matter (when worn properly). You breath through either a small filtration unit in the front of the mask or directly through the filtering material of the mask, NOT around the sides (as it should be sealed). The professional grade surgical masks that many of us have seen in the hospitals are loose fitting non-sealed masks that are designed to block the wearer from inhaling large droplets/splashes and to block their respiratory emissions (protecting others around them). They are not designed to prevent the wearer from inhaling aerosolized particles as they are not sealed around the edges (cdc.gov, crosstex.com). The final group are the cloth masks which can be made from various materials. Their main purpose is to allow more comfortable widespread facial covering for the general public; to reduce the inhalation of larger droplets and to reduce one’s own exhalation and aerosol creation. These types of masks are not specifically certified in any way, though I will discuss the research that has been done looking at filtration, efficacy and utility of the different materials.

So now on to how well do these different types filter out microparticles, specifically in regards to viral transmission (because that’s what’s on everyone’s mind). Numerous studies that compare N95s and surgical masks and how they prevent infection in hospital settings have shown both to be similarly effective when dealing with droplet based respiratory viruses like influenza (Randanovich 2016, Smith 2016). Laboratory testing of these two types of masks does confirm that the smaller the particle size, the better an N95 performs compared to a surgical mask (van der Sande 2008, Shakya 2016), thus they are more effective for those dealing with high level risk of aerosolized viral exposure. These two types of masks are certified, so it’s no surprise they perform fairly well, but what about the cloth and homemade masks? The first thing to consider is the type and thickness of material being use for the mask. Things that allow easy breathing or light to penetrate aren’t going to filter the air as efficiently, but if it’s too thick that you can’t breathe through it then it becomes extremely hot, uncomfortable and unwearable (and you breath around the sides, rather than through the material). One study comparing the filtration efficiency (of masks in a lab test, not on a person) of different materials found that items such as tea towels and cotton mixed fabrics did the best job of filtering particulate matter (up to 70% mean filtration) out of the air, while silk, scarves (like buffs), pillow cases and normal cotton T-shirts did not perform as well (45-60% mean filtration efficiency), with surgical masks being their standard (90-96% mean filtration) (Davies 2013). When commercially available cloth masks were compared to surgical masks on humans (again in a lab) filtration efficiency was more variable; with cloth filtering out 30-50% of microparticles while surgical masks filtering out 60-90% of microparticles and N95s consistently filtering out 80-95% (Shakya 2016). The efficiency of filtration directly correlated to the size of the particle, with cloth masks performing the poorest on particles small than 1µm in size. So that’s a little background about how the masks are INTENDED to be used and how they function in a laboratory, how about in real life?

Use in the General Public

By now you’ve probably heard many times that the public should not hoard or use N95s because we need them for our frontline workers (very true) and they don’t work for the public (partially true). The first piece is that because of the size of this pandemic we don’t have sufficient supplies of N95s for highly trained hospital workers who are coming into direct contact with the virus on a daily basis, thus need this heightened level of protection, first (and most important) reason not to stock up or hoard them. The second is that for an N95 to be at it’s most useful and functional you have to have it fit tested, you need to be trained in proper techniques to don/doff a mask and you have to actually use it correctly (you can’t be taking it off to talk, to eat, to drink, basically you can’t break the seal unless in a clean contained environment). They are also designed to be disposable, meaning you can’t wash them, though sadly our healthcare workers are being forced into extreme measures to try and sterilize/reuse them for lack of options. For the general public a surgical mask would be a descent option because they are designed to reduce droplet transmissions and to block one’s exhalations (protecting those around you), but sadly our hospitals are also short on these too, so for now they need to be saved for the frontline works (and patients) where they’ll do the most good. Also remember that both of these are designed to be disposable, so can’t be washed and aren’t designed to be reused for weeks on end (like the public would need).

So this brings us to cloth masks and their use in the general public. Mistakenly the US government (CDC) originally came out saying that cloth masks don’t work and that they aren’t necessary. By now most people have realized this isn’t exactly true, because why else would they change their minds and recommend people wear them? Yes, cloth masks are NOT designed to stop all tiny viral particles (and aerosols) from passing through, and yes they are not highly efficacious, but that doesn’t mean they don’t help. While a cloth mask won’t fully stop one from inhaling aerosols and microparticles, they do filter out some of the smaller aerosols (30nm-1µm) but more importantly block larger droplet transmission both inward and outward (Davies 2013, Shakya 2016). So while they do filter some of the air you’re inhaling, the major benefit of a mask is to protect those around you by minimizing the amount of aerosols you create. This is especially true with the knowledge that those infected with COVID-19 can be asymptomatic but still capable of spreading the infection. For masks to be most beneficial we all should wear them in any public setting where we’ll be interacting with others (even if we’re socially distancing).

Best Practices for Masks

Now on to a few personal suggestions for best practices when using a face mask. Note that much of this stems from my own personal training having worked in Biosafety Level 3 laboratories (blood and aerosol transmitted infectious diseases) and in hospitals, but some additional guidance can be found on the CDC website (CDC.gov). First off, once you’ve made/acquired your mask, put it on at home and work on the fit, comfort, breathability. A mask that doesn’t stay on or that you can’t semi-comfortably wear (to the point you’ll touch it a lot or take it off) isn’t very useful. Look to make sure it fully covers your nose and mouth, has a pretty good fit around the bridge of your nose and the sides, and that it won’t slip down when you turn/move your head.

Once you’ve established it works, wear it around for 20-30min inside your house to get used to the idea of breathing through a mask. It’s probably going to be a bit awkward at first, as for most people they’ve never had to do it before. This exercise will make it easier to wear in public without thinking about it too much. Now on to that more critical step, wearing it out. The main times the mask should be worn is whenever you’re going into a public area where you might have close contact with others. If you’re just sitting in your car and driving around, no need to wear a mask, but if you go to the grocery store, pharmacy, liquor store, gas station, work, or even walk around your neighborhood it’s best to wear the mask to protect those around you, even if you don’t think you’re sick.

To put on the mask, do so BEFORE entering that public space, meaning your home entry if you’re walking around the neighborhood or inside your car before you walk into a shop. Then clean your hands off so that you are less likely to contaminate other surfaces (hand sanitizer or washing). When you’re wearing you mask you SHOULD NOT be taking it off or moving it off your nose/mouth until you’re back in your non-public safe area. Wearing it half the time, pulling it down half the time, taking a break to eat or drink in public negates some of the benefits and protection and also adds to the chance that anything you pickup on your hands will be transferred to your face. When you’ve exited the public space, wash/clean your hands then grab the strings/band of the mask and remove it (do not grab the front of the mask itself). If you have a washable reusable mask proceed to wash it with soap and water. Disposable masks are supposed to be discarded into the trash (hence why not ideal for daily use in public). While your mask is your barrier of protection, remember it’s not foolproof, and is merely a way to further reduce your risk of becoming infected and infecting others. IT DOES NOT change the fact we should be social distancing and providing each other space or that we should be staying at/near home and avoiding any unnecessary travel/errands. Wearing a mask is just another tool in our arsenal to help slow the spread of the virus and reduce transmission rates.

One last note about gloves. Wearing gloves for most people in a public setting is useless (yes I said useless). Gloves are a very effective piece of PPE for trained healthcare and lab workers, but in our daily lives most people treat gloves just like their normal hands. They touch common surfaces, pick up food items, open doors, text on their cell phone, touch their mask, etc. All of these practices together make the use of gloves just as bad as dirty naked hands. You’re better off just considering your hands as dirty whenever you’re in public and not touching any of your personal belongings (including that cell phone) until you’ve cleaned them. If you have to touch your phone or food items while in public, there are many ways to also clean these surfaces as well. Don’t waste gloves and don’t touch your face.

Citations

Balazy et al. Do N95s respirators provide 95% protection level against airborne viruses, and how adequate are surgical masks. American Journal of Infectious Control, 2006.

cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/ppe/ppeslides6-29-04.pdf . CDC Guidelines for Selection of PPE in Healthcare.

cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/UnderstandDifferenceInfographic-508.pdf . Understanding the Differences, Surgical Masks, N95 Repsirators.

crosstex.com/sites/default/files/public/educational-resources/products-literature/guide20to20face20mask20selection20and20use20-202017.pdf . Guide to Face Mask Selection.

Davies et al. Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Awareness, 2013.

osha.gov/Publications/osha3079.pdf . OSHA Respiratory Protection Guidelines.

Randanonvich et al. N95 Respirators vs Surgical Masks for Preventing Influenza amount Healthcare Personnel. JAMA, 2019.

Sande et al. Professional and Home-Made Face Masks Reduce Exposure to Respiratory Infections among the General Population. PLOS One, 2008.

Shakya et al. Evaluating the Efficacy of Facemasks in Reducing Particulate Matter Exposure. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 2016.

Smith et al. Effectiveness of N95 Respirators vs Surgical Masks in protecting healthcare workers from acute respiratory infection: a systematic review and meta analysis. CMAJ, 2016.

Thank you for this great info. Can you provide any info on the use of respirator masks that use charcoal filters?

Belinda,

This is a good question. I didn’t include any information about activated carbon (aka charcoal) filters because the charcoal filter itself is designed to filter out gases and not specifically designed for viruses and infectious diseases (nor tested against such). Some masks with charcoal filters are also N95 rated so that would be ideal. Even if the mask wasn’t N95 rated it would effectively function more like a cloth mask filtering out larger particulate matter and droplets. I haven’t seen any direct testing comparing a non-N95 charcoal mask to cloth masks so unfortunately can’t give you any direct numbers.

Eric